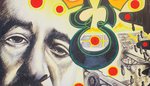

Antonio Dattorro ate garlic to survive in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. He returned home, lived his life and eventually put paint to canvas.

Dattorro lived from Sept. 21, 1918 to March 31, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account by clicking here.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

|

Antonio Dattorro ate garlic to survive in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. He returned home, lived his life and eventually put paint to canvas.

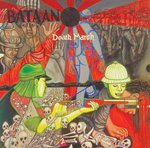

Dattorro lived from Sept. 21, 1918 to March 31, 2001, was a Rhode Island artist whose last project was to recreate with charcoal and paint the terror of the infamous Bataan Death March (BDM) and what he later witnessed in the prisoner of war (POW) camp during the more than three years of his internment.

He did this work between 1979 and 2001. In November, 2021, the New Mexico Military Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, accepted eight of his paintings for exhibition.

In 1997, under the leadership of Major General Reginald A. Centracchio, there was a showing of Dattorro’s POW works at the National Guard Readiness Center in Cranston.

He was raised in North Providence, and joined the Army Air Corp on Sept. 19, 1940. At first he was stationed in Australia and Hawaii. Then Dattorro was stationed at Bataan on the Island of Luzon in the Philippines. Bataan fell to the Japanese on April 9, 1942. After the Bataan Death March, during which many Americans were murdered, he was taken to the Zentsuji POW Camp in the Kagawa Prefecture of Shikoku, Japan.

Dattorro was a prisoner there for more than three years. When the Atom Bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, the Japanese guards abandoned the camp. Japan finally surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945.

Dattorro started the march weighing 170 pounds, and came home weighing 86 pounds. He received a broken back by a guard jumping on him, teeth knocked out by being hit with a rifle butt and a pierced arm by a bayonet. Dattorro received two Bronze Stars, two Purple Hearts and the Rhode Island Cross for his service.

He credits the garlic he ate, which was planted among the crops in camp, with helping him survive.

Upon his return to Rhode Island, he met and married Jennie (Russo) and had two sons, Anthony and Jon.

Dattorro attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) where he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting in 1951 and a Bachelor of Science in Education in 1953. He was hired by the Providence Public School Department in 1952 to teach art at Hope High School until 1979.

In 1977, Antonio displayed a 300-feet-long continuous painting by the side of his street, Barbara Ann Drive in North Providence. The work chronicled his life, his family and commentary on world happenings. On April 9, 1978, he established an Art Gallery within Hope High School, and mentored many students, directing them toward art schools. In one year, four of the 10 Rhode Island students accepted to RISD came from his art class. Kate Huntington was one of his very successful students.

Dattorro said, “I decided I would do only paintings and drawings that couldn’t be sold”.

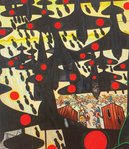

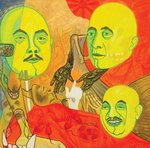

Antonio retired in 1979 and eventually drew and painted some of his recollections of the Bataan Death March and his three years as a POW in Japan.

After his death in 2001, his son Anthony, who was living in Las Vegas, had Antonio’s paintings stored in a facility in West Warwick. Last July, 2021, I received a phone call from Anthony telling me to go to the storage facility and take any paintings I wished. Anything left in the building after Aug. 16, was to be destroyed.

My friend, Allan Carter, and I went to the facility, an old brick mill filled with hundreds of storage units. We saw there were too many large paintings for us to take. I discussed the situation with my companion, Eloise Weston. We remembered that her daughter, Eloise Malloy, was friendly with William Miller, a faculty member in painting at RISD. Malloy and Miller went to the storage facility and saw that they couldn’t remove the paintings due to their size. William returned with some RISD students and a U-Haul.

Salvaged were five individual paintings and a series of eight paintings that depicted what Dattorro saw as a POW in Japan. William had the professional photographer at the RISD Museum take photos of the series of eight paintings.

William contacted the appropriate people in Santa Fe at the New Mexico Military Museum, previously named the New Mexico Bataan Museum. He sent the eight photos to them for consideration. In November, 2021, we received word from the acquisition committee that they would accept the paintings for display in their museum.

On Jan. 3, 2022, the paintings were put in crates built by Miller and RISD students and loaded on a truck to be delivered to the New Mexico Military Museum.

Antonio Dattorro’s legacy will live on for others to see the horrors he and fellow American service men experienced.

Editor’s Note: Stanley Freedman, a Johnston resident, wrote this story about his experience attempting to save the artwork of Antonio Dattorro. He hopes to bring Dattorro’s artwork to a wider audience, so people can see what one lost veteran artist experienced while surviving the horrors of war.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here